This is an archived website, available until June 2027. We hope it will inspire people to continue to care for and protect the South West Peak area and other landscapes. Although the South West Peak Landscape Partnership ended in June 2022, the area is within the Peak District National Park. Enquiries can be made to customer.service@peakdistrict.gov.uk

The 5-year South West Peak Landscape Partnership, 2017-2022, was funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

The Church of St Lawrence in Warslow: A Guided Tour

Posted on 5 June 2019

The latest in a series of blog posts chronicling the adventures of our Cultural Heritage Officer; Dr. Catherine Parker Heath. In this installment she recounts an elucidating tour of the Church of Saint Lawrence in Warslow by South West Peak Landscape Partnership Volunteer Maggi Rowland.

The Church of St Lawrence, Warslow

On Monday 29th April, several South West Peak Volunteers attended a wonderful tour of the Church of St Lawrence in Warslow led by another SWP volunteer and Volunteer Ranger, Maggi Rowland.

Maggi gave a brief overview of the early history of the site, then concentrated on giving us a detailed insight into the building of the existing church and its subsequent history.

Maggi Rowland leading the tour of St Lawrence’s

Most of the current church, in fact all except the altar end, was built in 1820s. This falls within what is known as the Georgian Period and the style of the period is reflected in the architecture of the church with tall arched windows along each side. It would have had box pews at that time, very much like those in the Church of St John the Baptist at Upper Elkstone, albeit on a much smaller scale there. At this time the church at Warslow was dedicated to St James, only becoming dedicated to St Lawrence in 1850.

The fortunes of the church at Warslow went up and down according to what was going on in Warslow and that depended to a large extent on what was going on at the nearby mines, such as Hayesbrook Lead Mine opposite Warslow Hall, and Ecton Mine and Dale Mine on either side of the Manifold south of Warslow. In 1851, there were 854 people living in the village. Currently there are around 200. When we translate that to numbers in the congregation: today, around 6 to 8 people attend church (4%) whereas in 1851, 200 attended on census day, which is around 25% of the population.

In the later Victorian period there was a renewed interest in Christianity across the country. At Warslow, this led to the church being expanded and refurbished around 1900, including the building of a new chancel. The refurbishment of the church is a wonderful example of the local community and great benefactors (who were renowned nationally) coming together.

Warslow and the Harpur Crewes

In 1900, Warslow, of course, had the church and opposite it was the school. It also had seven pubs and near one of those, the Greyhound Inn, was the Cattle Market. Much of the land around was owned by the Harpur Crewe family of Calke Abbey (south of Derby, now a National Trust property). The Harpur Crewe family had built Warslow Hall in 1830 for the manager of their Warslow Moors estate. However, the family decided they wanted it for themselves as a base for hunting and fishing. In 1900, the head of the family was Sir Vauncey Harpur Crewe. He was married to Lady Isabel and they had five children. Every August, the family came to Warslow Hall and occupied it for the shooting season and they were often at Warslow Hall for Christmas too. They were, by all accounts, a rather eccentric family: their Calke Abbey residence is known as “the house where time stood still” as the family was reluctant to spend any money on improvements -apparently, Sir Vauncey was against all new-fangled things. He also preferred to write notes to his family rather than speak to them. Lady Isabel was on the other hand very sociable. But despite their differences, they were both active members of the church at Warslow. In the church today you can see the Harpur Crewe pew where the family would sit at Sunday services and watch to see who attended. Tenants were expected to attend church but this was unpopular with the farmers, perhaps understandably, who still had farming to do, even on a Sunday!

The Harpur Crewe Pew

It was with the support of the Harpur Crewe family, Lady Isabel particularly, that the refurbishments took place. Lady Crewe worked hard to raise funds for the works, holding bazaars, sales of work, concerts and so on. She was very much in favour of a new chancel but Sir Vauncey, with his reluctance for all things new, was not. In fact, once the new chancel was built he never again stepped one foot into the church.

Warslow and the Wardles

It may be that the very idea for the refurbishment and the building of the new chancel came from a man named Sir Thomas Wardle, from Leek. Sir Thomas was what can be described as a Great Victorian (and Maggi’s hero!). He had two silk dyeing works in Leek, inherited from his father Joshua, which used the waters of the River Churnet, renowned for being clean and pure, to dye silk. Sir Thomas was particularly interested in natural vegetable dyes and became an expert, never once using chemical dyes. He was very interested in Tussur silk from India, which was difficult to manufacture because of its tough outer filament but through trials and experiments he got to grips with it. In fact, Sir Thomas became an expert in everything he dabbled in, just as he had with Tussur silk. He loved the area around Warslow. He fished in the Manifold, explored caves along this river and the River Dove. He was also an archaeologist and palaeontologist and discovered a previously unknown fossil fern on Butterton Moor. It’s a wonder he could fit it all in especially considering he and his wife, Lady Elizabeth also had nine children (or rather had nine that survived out of thirteen that were born).

In 1896, Thomas Wardle bought Swainsley Hall in the Manifold Valley as a country retreat. The mines at Ecton were not long closed and it is interesting to consider what the landscape might have looked like at the time – a derelict industrial wasteland? Well, certainly something different from what we see today. He extended the house to fit in his large family and when he stayed there he would come to the church in Warslow. He played the organ and trained the choir. In 1900 the idea of the new chancel came along. One reason why it is suggested that it was Thomas’s idea is because his family came from Cheddleton and he had been involved in the refurbishment of the church there. Whatever the truth of this, he was certainly active in the refurbishment of St Lawrence’s and supported the project practically and financially.

Lynam, Riley and Lloyd

A friend of Thomas Wardle was the architect for the new chancel - Charles Lynam. Lynam was the architect for the Diocese of Lichfield and as well as being a friend of Sir Thomas, he was also a keen archaeologist. Maggi regularly monitors Scheduled Ancient Monuments and said she often comes across Charles Lynam’s name on information sheets referring to local barrows surveyed and listed by him.

The builder was a local man named Edwin Riley who lived in the house next to the Church (he was also the local undertaker). The landlady of the Greyhound Inn at the time, Mary Lloyd gave two bells to complete the three bells needed. Two had been lost previously. The Georgian box pews were stripped out of the church and used as paneling on the new organ chamber.

Georgian box pews recycled as panels on the new organ chamber

Sir Thomas Wardle, William Morris and the Stained Glass Windows

Sir Thomas also had a strong business relationship with William Morris. In the 1870s William Morris was developing his printing works and wanted to use vegetable dyes. Consequently he had stayed with Thomas Wardle in Leek from 1877 to 1879 to learn from Wardle’s expertise, especially in the use of indigo dye. One of Thomas’ dyeing works became dedicated to producing William Morris’s prints; Thomas Wardle was in fact the first printer of several of William Morris fabrics. William Morris founded Morris & Co. along with three or four of the great designers of the time who belonged to the Pre-Raphaelite movement. A furnishing and decorative arts manufacturer and retailer, they also designed and made stained glass windows.

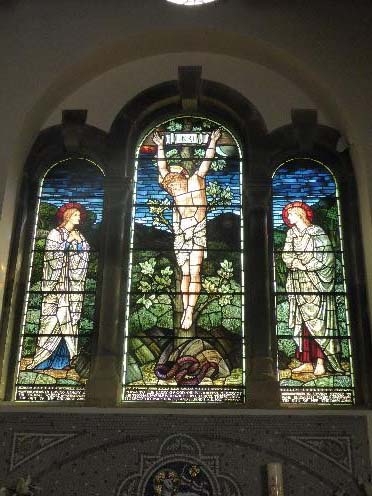

Because of the connections of Sir Thomas Wardle has, it is perhaps unsurprising then that five windows in the church were designed and made by Morris & Co. – quite a treasure for a little village church, many with an Edward Byrne-Jones’ design, such as the Memorial Window celebrating the Great War showing St Michael. Another window (Jacob’s Dream) was made in memory of Richard Harpur Crewe. Sir Thomas and his wife Elizabeth paid for each side of the altar window and the central piece was paid for by the villagers (Christ on the Living Tree with the Virgin Mary and John the Apostle). Mary Lloyd, the landlady of the Greyhound Inn also paid for two of the stained glass windows (Christ the Sower and St Lawrence) in memory of her husband and all five children whom she outlived.

The Memorial Window

Jacob’s Dream

The Altar Windows: Christ on the Living Tree with the Virgin Mary and John the Apostle

Christ the Sower

St Lawrence

The Opening of the New Chancel

The new chancel was opened in 1908. A big service was held, attended by the Bishop of Lichfield. A procession included the Warslow band and people sang hymns as they walked. It was Thomas Wardle who had composed the music. And there was a write up in the Leek Post.

Exterior view of the chancel with date stone of 1908 below the arched window

Internal view of the chancel from the gallery

Even so, work was not yet complete. A full set of four altar frontals was commissioned by Lady Isabel Harpur Crewe on the opening of the new Chancel. They were made by the Leek Embroidery Society in liturgical colours, using silk and dyes made by Sir Thomas. It was Sir Thomas’ wife, Lady Elizabeth, who was instrumental in bringing them to fruition. She, an accomplished embroiderer, was the founder of the Society in 1879, and she trained young women in the necessary skills using the silks and dyes produced by her husband to make the cloths.

One of the altar frontals

Unfortunately, Thomas Wardle himself died in January 1909 soon after the opening of the chancel, but nonetheless leaving a great legacy behind him. He had made provision in his will to fund any of the outstanding expenses of the building of the chancel.

Regarding the mosaics around the two side windows in the chancel, very little is known about them. They are, as far as is known, unique. It is suggested that they were made by Italian prisoners of war during WWI who had been billeted at Sheen, but there were no Italian prisoners of war in WWI as Italy was on the side of the Allies and no records exist of any prisoners of war in Sheen. It is interesting to consider how such tales come into being.

The altar mosaic, we know more about. This was made in the 1960s and specifically designed to match the window mosaics.

The altar mosaic

It was a fascinating tour. A church can often seem to be very much the same as another, having constituent parts that make up every church, such as a nave, chancel, bell tower, stained glass windows and pews. But even if architecture and fittings can be the same, the stories of the people that created them never are. They should be remembered and told. Thank you Maggi for doing this.

To learn more about the Cultural Heritage projects the South West Peak Landscape Partnership is running please head over to our Barns & Buildings and Small Heritage Adoption project pages.